The 9 December EPSCO meeting in which the Commission was going to make its big reveal to fix the MDR came and went and left many people with a lot of conflicting emotions, but not that much concrete to go on. It seem that this is the way of the MDR, piecemeal definite maybes.

There was the weird reference by Commission to the Russian invasion in Urkraine as a contributory cause of delays with the MDR somehow. That had me raise my eyebrows. I don’t know what the Commission was trying to achieve with this.

There was the proposal announced that remained announced until early January coming year, and that will still likely look like outlines set out in the Commission’s briefing note for the EPSCO meeting.

And, finally, there was the announcement of the announced bridging measure for the expiring certicates that expire pending MDR conformity assessment. This dropped right after the EPSCO meeting in the form of MDCG 2022-18, a new position paper on the application of article 97 MDR.

Let’s take a look at where we are on these points.

Proposal for MDR and IVDR

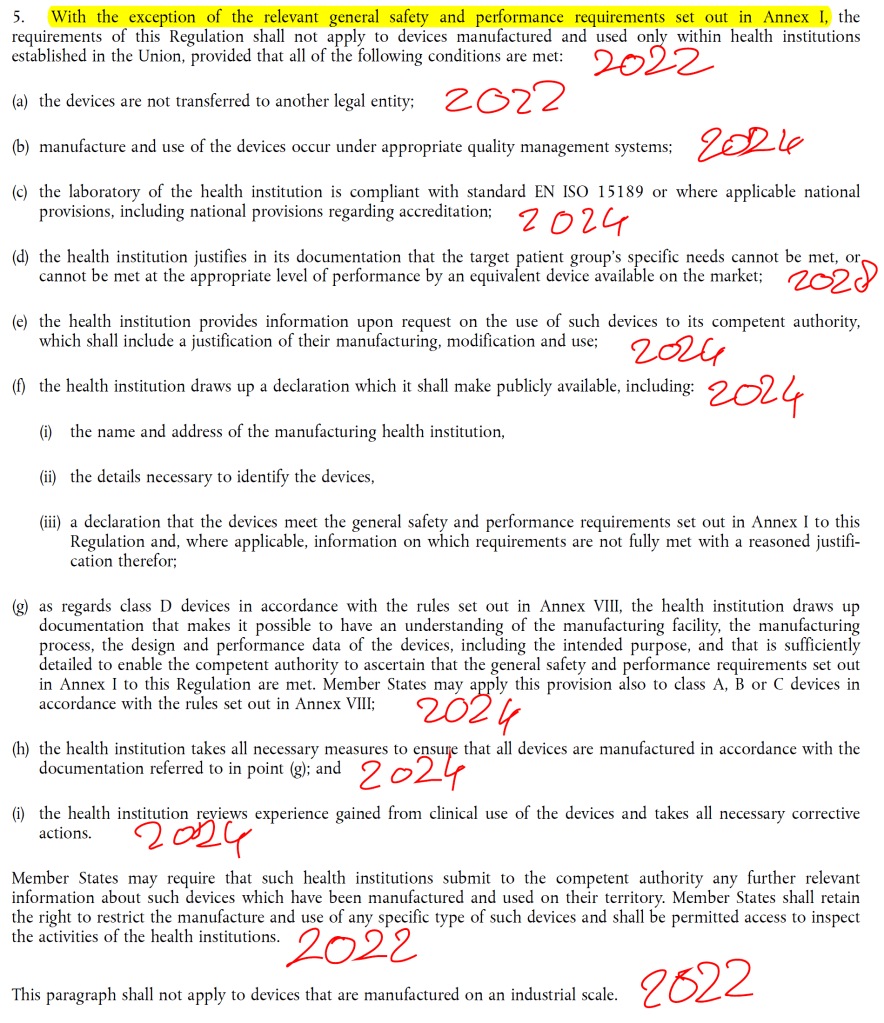

Note that the Commission proposal covers both the MDR and the IVDR (for the IVDR: removal of sell-off period only). The outlines of the proposal as provided by the Commission are (which are still not 100% certain until we’ve seen the final proposal, the Commission still calls them “likely elements are based on the input received so far from national experts and stakeholders”):

- An extension of the transitional period in Article 120(3) MDR [beyond 26 May 2024] for legacy devices in scope of article 120 (3) MDR with staggered deadlines depending on the risk class of the device. Those deadlines could be 2027 for class III and class IIb devices (i.e. devices with a higher risk) and 2028 for class IIa and class I devices (i.e. lower risk devices) that need the involvement of a notified body in the conformity assessment;

- If needed for legal and practical reasons (including for access to third country markets), the extension of the transitional period could be combined with an extension of the validity of certificates issued under Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC by amending Article 120(2) MDR;

- Conditions to be fulfilled in order to ensure that the extension applies only to devices that do not present any unacceptable risk to health and safety, have not undergone significant changes in design or intended purpose and for which the manufacturers have already undertaken the necessary steps to launch the certification process under the MDR, such as adaptation of their quality management system to the MDR and submission and/or acceptance of the manufacturer’s application for conformity assessment by a notified body before a certain deadline (e.g. 26 May 2024);

- The removal of the ‘sell off’ provision in Article 120(4) MDR and Article 110(4) IVDR.

The extension would likely provide that legacy devices would need to transition to the MDR by risk class and subject to conditions under point 3:

- Class III – 2027 (date not specified yet);

- Class IIb – 2027 (date not specified yet);

- Class IIa – 2028 (date not specified yet);

- Class Im, s and r and up-classifieds (e.g. class I software) in scope of article 120 (3) MDR – 2028 (date not specified yet) (Note that devices that are ‘normal’ class I under the MDR are not in scope of this transitional regime, this is an often made mistaken assumption by class I devices manufacturers, so inform yourself here).

Conditions for the extension:

- devices must not present any unacceptable risk to health and safety;

- devices have not undergone significant changes in design or intended purpose;

- manufacturers have already undertaken the necessary steps to launch the certification process under the MDR, such as adaptation of their quality management system to the MDR and submission and/or acceptance of the manufacturer’s application for conformity assessment by a notified body before a deadline still to be proposal (e.g. 26 May 2024).

In summary, the extension is only available for devices that are already subject to the ‘necessary steps to launch the certification process under the MDR’, of which we do not know what this exactly means. It can be that the manufacturer has adapted his QMS (that’s an example given by the Commission) or it may be that the actual acceptance of the application of the manufacturer by the notified body for conformity assessment is adopted as condition (another option mentioned by the Commission).

But there is a wide gap between these two, and one is under control of the manufacturer himself while the other is not. One is a binary criterion (application accepted by NB) whereas the other is very much subject to interpretation (QMS MDR ready or not). Accordingly, there is a massive degree of uncertainty still because different choice of criteria will have very different consequences for the group to which the transitional period extension wil be available. If the criterion will be acceptance by a notified body, this will do little to solve the bottleneck because notified bodies are not going to accept a lot of extra applications in the near future because they are still strapped for resources. On the other hand, if the criterion is going to be QMS MDR ready, who is going to check if the QMS is ready enough? The member states? They don’t have the capacity for that. So the Commission still has a very difficult choice to make here. We’ll need to see what they end up proposing.

Removal of the sell-off period sounds like a good idea to not put extra strain on the supply chains because one year under article 120 (4) MDR and 110 (4) IVDR was a very short sell-off period that was going to pose problems many companies because devices often just do not move through the supply chain this fast. This will allow companies to sell-off devices more gradually but does not solve the problem that they will need to have the devices concerned placed on the market in time for the 26 May 2024 deadline for the MDR, which does not seem to move for this purpose. The proposal would also concern the IVDR sell-off period for IVD devices subject to an IVDD certificate (not that many on the total), allowing the manufacturers of those also a smoother sell-off period.

Will article 120 (2) MDR be amended (point 2 of the proposal) as to allow a long certificate duration for directive certificates? That would be something but it would also be spectacularly unfair to the manufacturers with directive certificates that already have expired causing them to cease placing the devices concerned on the market pursuant to expiry of the certificate. The Commission would, in my view, also need to look at options to revive expired certificates. Of course, we will need to see what the Commission means with “if needed for legal and practical reasons (including for access to third country markets)”. For example, the MDCG 2022-18 position paper discussed below contains a solution for this problem, including for access to third country markets (not the best though, so this solution might be better). Hard to say therefore how the Commission proposes to fill this in given the MDCG 2022-18 options. But it would provide for another tool in the toolbox to deal with certificates expiring during conformity assessment.

So do we have an ‘extension’ now? No, not quite yet – the Commission will formally make the proposal in early January according to the Commissioner. Do we know what it will look like exactly? No, neither – just the general lines but as discussed there are still important open points. We have to wait for the final proposal to know for sure.

MDCG position paper for article 97 MDR

This part of the package is an MDCG position paper MDCG 2022-18, meaning that this is the member states talking and implementing. We had already seen that earlier position papers MDCG 2022-11 and 2022-14 hinted at article 97 MDR measures and now this is the result.

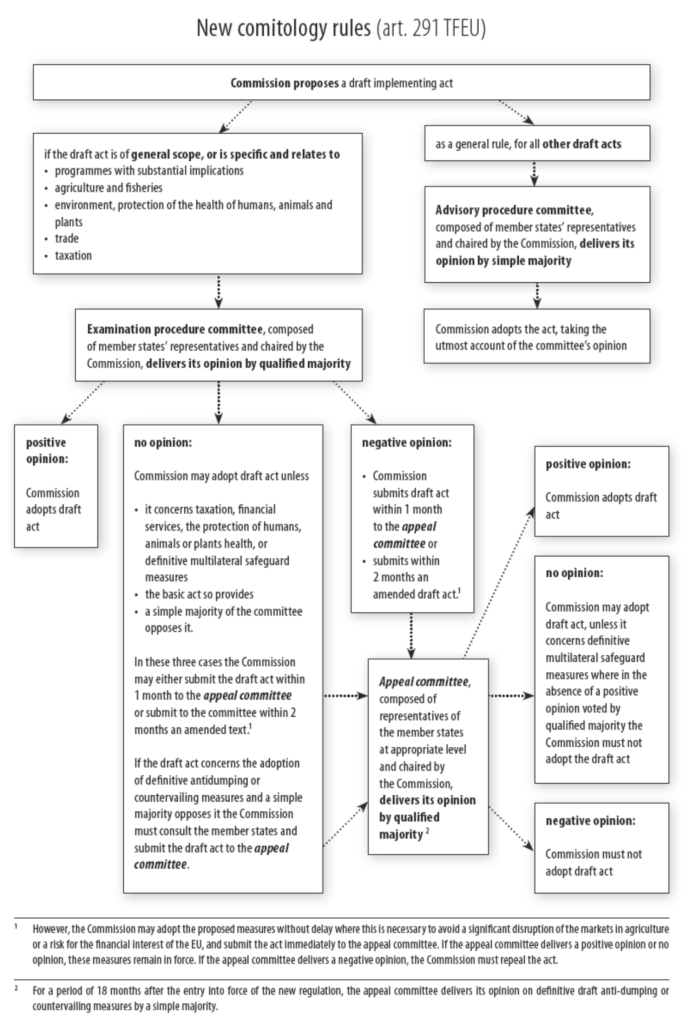

Readers should note that the MDCG is not introducing something new from a legal perspective, because the article 97 (1) MDR instrument has always been in the MDR and available to the member states that wanted to use it. Some have also issued exemptions under article 97 MDR already. The position paper is merely guidance on a coordinated set of criteria and approach that the member states intend to use for this. That could have also been done by means of formal harmonization by means of an implementing act under article 97 (3) MDR (a cleaner measure with higher degree of legal certainty if you ask me) but the member states have opted not to limit their individual discretion too much apparently. So now we have a position paper with loosely drafted guidance, still allowing each member state to pretty much do what they like and ask for the documentation they like to see (MDCG documents are non-binding, remember?).

However, the big step forward of this position paper is that member states will recognize article 97 (1) MDR decisions issued by other member states, much like the mechanism with orphaning under the directives (as I predicted that this could look like last summer, which now indeed turns out to be the option chosen). This means that one application will suffice for the entire Union territory (Union is not the same but larger than EU, mind you). On the other hand, if your application is rejected, don’t expect local article 97 MDR love from individual authorities in the Union. The good part of this procedure is also that it is available to manufacturers with certificates that have already expired.

To whom and how is this procedure available? MDCG 2022-18 gives the following cumulative conditions:

- Apply in the member states of the manufacturer or the manufacturer’s authorised representative;

- Legacy devices in transition, meaning devices actually in conformity assessment of for which, despite reasonable efforts undertaken by the manufacturer to obtain certification under the MDR, the relevant conformity assessment procedure involving a notified body has not been concluded in time, and the certificate expires;

- No other non-conformities than certificate expiry;

- No unacceptable risk to health or safety of patients, users or other persons, or to other aspects of the protection of public health (to be demonstrated by the manufacturer by means of a report containing relevant data gathered through its post-market surveillance system (PMS), in particular data concerning incidents, serious incidents and/or field safety corrective actions);

- Limited temporal exemptions – competent authority defines duration of exemption, default is 12 months, option to be extended in ‘duly justified cases’;

- Manufacturer should already have undertaken reasonable efforts to transition its device to the MDR (manufacturer’s application for conformity assessment under the MDR should have been accepted by a notified body and a written agreement signed by notified body and manufacturer in line with section 4.3 of Annex VII MDR). In duly justified cases, the CA may waive this condition, in particular where the following conditions are all met: (i) the manufacturer is a SME, (ii) MDD or AIMDD certificate of that SME manufacturer had been issued by a notified body not (yet) designated under the MDR, (iii) the SME manufacturer can demonstrate that it has undertaken reasonable efforts to apply to a considerable number of relevant notified bodies and that their application has not been accepted due to limited notified body capacity;

- The device should not be subject to any change as regards its labelling, including CE marking.

You may have issues convincing other non-Union authorities about the validity of the CE certificate if you are relying on an article 97 MDR exemption. The position paper states that certificates of free sale may still be issued in accordance with national provisions with a validity that should not exceed the period by when the manufacturer should bring the device in compliance with the MDR. That will be a lot of administration because you will have to set up a yearly review cycle with foreign authorities and will need to spend a lot of time explaining them how this works. We’ve seen throughout the implementation of the MDR and IVDR that the transitional regime (which keeps changing too!) is very hard to explain to other authorities in countries that rely on the CE mark for national registrations. The EU is really not doing itself a favor by eroding its soft power in the world with a reliable and predictable regulatory system for medical devices that can serve as a reliable platform for local registrations. We see the first signs of countries moving towards the US system for this (Australia, Switzerland).

It is nice that the position paper sees the plight of SMEs. However, this proposal does nothing to help SMEs going to the market for the first time after 26 May 2021, it is oriented to SMEs that have a notified body that is not notified yet, rather than a notified body that is MDR notified but simply has not started the SME’s conformity assessment process yet and/or will not finish in time (more common). SMEs will fortunately have the option to approach the authorities with their issues and hope for an article 97 exemption. So it’s something for SMEs but nothing big.

The big unknown of course is where the competent authorities are going to get the capacity from to be able to assess all these applications and churn out exemptions reliably and predictably in a reasonable time frame. As far as I can tell, none of them is adequately staffed to this, which will mean delays in processing article 97 MDR applications in many places, especially those where most of the manufacturers and authorized representatives are clustered.

Another unknown is how this position paper relates to the Commission’s potential proposal to extend article 120 (2) deadlines for back stop date of certificate validity of 26 May 2024 to a date potentially beyond that, as was discussed above.

Note: article 97 MDR is not the same as an article 59 MDR derogation! These latter ones are much harder to get because you need to provide that the device is indispensable for public health and that there are no real alternatives on the market for your device, which is not that easy to do in practice.

If you need help with your article 97 applications or thinking about strategy around then, I’m here for you.

And then there still is the MDCG 2022-14 19 points position paper

Then there still is the MDCG 2022-14 position paper with many points intended to free up notified body capacity and/or make the MDR and IVDR system run more efficiently, some of which make sense and others make less sense (see my analysis of it).

What we are seeing now is that notified bodies are responding to the new room given by stepping up and have started to issue Team NB guidance such as the Best Practice Guide on technical documentation, Team NB position paper on implementation of MDCG guidance and the work on a position paper on leveraging directive conformity assessments to establish compliance with the MDR requirements.

Also the MDCG is rolling out items, for example with the new MDCG guidance on hybrid audits, but the MDCG being the MDCG, this will be a slow and ponderous step by step process.

There still is a lot to do, and the MDCG would also do well to keep the market informed to what the member states themselves do and achieve as to not to remain ongoing part of the problem, such as speed up notification assessment processes, speed up medicinal products assessments, staff article 97 MDR exemption processes adequately and the like. These are all factors fully under control of the member states themselves so member states have all the options to speed up these processes and be part of the solution themselves.

Conclusion

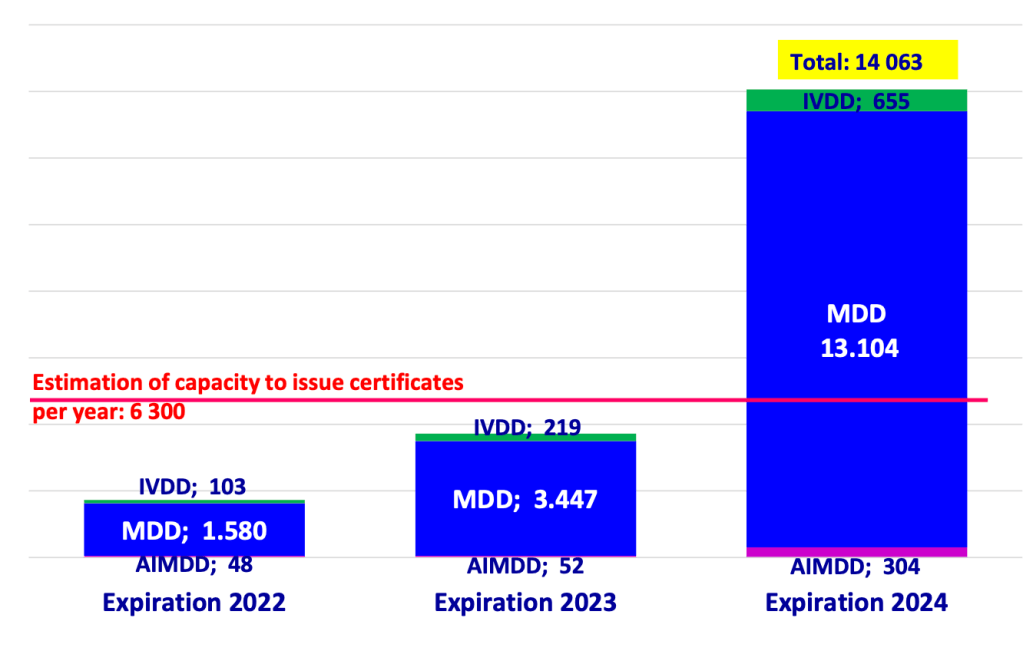

Too little? Hard to say at this moment. Too late? Absolutely. The writing of this transitional regime breakdown was on the wall since 2018-2019 when the majority of certificates was renewed all the way to 26 May 2024. People like me have warned publicly at that time about the consequences of these choices. This was where the market, notified bodies and authorities chose to put all of this on the roulette table, hoping for the best for notified bodies being able to sort this out. But that best did not materialise. And now we need to clean this up. With the structural under-resourcing of medical devices policy and market surveillance this is a piecemeal process as we are seeing, but also the result of conscious choices for which no-one else is to blame than the member states that decide on resourcing of the Commission and their national authorities for implementation and the EU legislator that designed this system.

You would think public health is more important, but apparently it is not. You would think that the public health ministers of the member states would be comfortable going on the record to explain that the system does not need more resources to function (which I assure you they are not because they know differently). As I’ve said before, apparently it first needs to get way worse before it can get better. The patients (which we all are potentially by the way) deserve so much better from the system. And it is such a sad way to put a major dent in Europe’s historically stellar international reputation as a soft power in regulation of of medical devices and IVDs.

What should companies do? Well, they make a plan and they follow through. We know a lot more, so now it’s time to determine which of your devices in MDR transition fall in which options bucket and what the potential options are. The options are not final because we are waiting for the proposal to drop early next year, but you can work with the outlines already.

Companies that had planned to push all their product to end users before 27 May 2025 can cautiously start to plan to relax this effort now because the hard stop at of the sell-off looks to be removed (but wait for the final proposal to be be adopted to be sure!).

As said, if you need help making sense of all this, I’m here for you.